By Alexis Hauk

When the eighth bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta, the Rt. Rev. Frank Kellogg Allan, died on May 24, he left behind him a wealth of stories that could easily take years to collect and distill.

Frank Allan’s roughly half-century career spanned an era of accelerated social progress — including desegregation in the South, and the Episcopal Church’s ordination of women and expanded embrace of the LGBT community. An article about Frank’s life published in the Atlanta Journal Constitution on June 2 succinctly laid out the highlights of his bold initiatives, which included setting up a network of safe homes for children during the Atlanta child murders of 1979-1981, starting the Folk School at Camp Mikell, and launching the nonprofit Work of Our Hands.

There’s also the crucial work Frank and his wife, Elizabeth, did upon their arrival in Macon in 1968, a volatile year bookmarked by the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy—a time when the “whole world was watching” as protesters were beaten viciously at the Democratic National Convention, and when the Vietnam War was raging, seemingly without end.

During those challenging times, as rector of St. Paul’s parish in Macon, Frank and Elizabeth “demanded inclusion,” as longtime friend Joni Woolf put it. During the Allans’ nine-year tenure at St. Paul’s, Woolf said Frank strived to remind the comfortable, predominantly white congregation that “there’s a world out there” — and that the church and parishioners should wake up and get to work trying to help that world.

In a testament to the breadth and reach of his impact as priest and then bishop, a post he served from 1989 to 2000, some 450 mourners attended Bishop Allan’s memorial service at the Cathedral of St. Philip on June 1, with countless others tuning in to the livestream from around the world.

Since Frank’s death, Elizabeth has marveled at the outpouring of gratitude and admiration people have shared with her—stories about how her late husband, her partner for more than six decades, changed their lives.

“I’ve been reading a lot of notes with things people said he said or did that I never knew about, because he was very private about that,” she said.

As true of many epics, a dynamo love story lies at the core of Frank’s biography, an intertwining of two souls that spanned just shy of 62 years.

Elizabeth and Frank Allan not only worked as a teacher/minister dynamic duo across Georgia and Tennessee, but they also managed to raise four children together: John, Michael, Libby and Matt — all born in quick succession in five years. And Elizabeth and Frank would later delight in their nine grandchildren.

Frank and Elizabeth met during summer school at Emory University. Elizabeth Ansley was a student at Agnes Scott College, the women’s school in nearby Decatur, and decided, almost on a lark, to enroll in some summer classes because “a coed school might be kind of fun.”

She sat down on the first day of her modern Russian history class at Emory, and almost immediately a dapper young man dressed snappily in a white dress shirt took the seat next to her and struck up a conversation. About halfway through their chat, he asked her out. That man was Frank Allan, an English major with a penchant for history, a perfect yin to Elizabeth’s yang as a history major with a voracious appetite for literature.

Their Russian history class turned out to be less a tutorial in what was then the Soviet Union, and more a look back on the works of Dostoevsky — a romantic atmosphere primed for this flourishing new love. And yes, Elizabeth added with a smile, “I had read the textbook and Frank hadn’t, so I made an A and he made a B.”

Before too long, Frank had worked enough hours at his afternoon teaching job with a nearby elementary school to save up for an engagement ring.

Although they had both grown up Presbyterian, Frank had begun to feel drawn to Episcopalianism. Despite his early ideas about becoming a lawyer after graduation, he decided to pursue seminary at the School of Theology at The University of the South, and together, Frank and Elizabeth pivoted into living through faith on a more tangible level.

Their wedding at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Decatur took place almost exactly one week after Elizabeth graduated from college. It was a simple affair, with the ceremony at 7 p.m. followed by a brief reception with fruit punch, wedding cookies, and green and pink mints. That’s just how things were done then.

One of the first of many moves in response to Frank’s calling, Elizabeth remembers, was a summer seminary post in Interlachen, Florida, where Elizabeth taught Vacation Bible School. It was a tiny, dusty town where alligators glided “back and forth across the sandy road.”

Not born to stay put, they then moved Dalton, where all of the Allan kids were born. Then up to Tennessee. Then finally to Macon, where destiny stepped in.

Rev. Martha Sterne, the first female priest Bishop Allan ordained after becoming bishop, delivered the homily at his funeral. Don’t call it a “eulogy,” she explained, because of the grandiose, overwrought speeches of glory Frank felt that particular word implied.

The winking wit and humor evinced in Martha’s words about her dear friend and colleague — “Frank stories,” as she put it — evoked the complexity, depth and warmth inherent in encounters with him.

She remarked: “He opened new doors for women. He could not carry a tune in a bucket — and didn’t seem to know that. He showed up at parishes when the going got rough… He learned from his dogs. He preached and taught spaciously, not prescriptively. He could laugh at himself. This worked best if he laughed first.”

With Work of Our Hands, Martha Sterne wrote, “He and Elizabeth found together that making art stirs the holy and creative spirit in thrilling ways that cross all boundaries and walks of life.”

One of the greatest difficulties during the last few years of Frank’s life, as he struggled with illness, was the erosion of autonomy. He was used to simply getting things done — even down to cutting his own hair for most of his life.

Of course, he didn’t just do things himself but motivated others to act with the same autonomy and conviction. Joni Woolf, the parish secretary when Frank started at St. Paul’s in Macon, sums up his legacy this way: “He was prophetic.”

Part of his ability to get things done, and to urge those around him to follow suit, may have derived from his gift of language. “He was, for many of us, and I’ve never heard anybody contradict me on this, the best preacher I’ve ever heard,” Joni said. “He never preached a bad sermon. Never.”

“He wasn’t a touchy-feely person at all, but he was so righteous. Without being self-righteous,” she said. “He was willing to be almost spit-upon to do what he believed was right. When somebody’s that committed, you say, he must believe in something bigger than himself.”

That commitment to something bigger — call it the Gospel — led him to welcome refugee families to community in the name of Christ and to encourage the leadership of children and youth in church. (Such as the “folk mass” Frank held with youth in the community, complete with banjos and guitars and even tie-dyed robes.)

St. Anne’s in Buckhead is where Andy Smith first encountered the Allans when Frank transitioned there from Macon in 1977. Andy’s wife, Glenna, was Frank’s parish administrator at the church and then continued to work for him when he became Bishop. The Allans and Smiths over the years became steadfast friends.

But their first interaction as priest and pastor wasn’t run-of-the-mill. It occurred under high-stakes circumstances, when the Smiths’ second daughter, born with a septal defect of the heart, was undergoing life-saving surgery. Frank joined Andy and Glenna at Egleston Children’s Hospital during the agonizing early morning hours when their infant’s life hung in the balance. He stayed with them, prayed with them, and ached with them.

“That’s when you really get to know someone,” Andy Smith said. “As a parent, you’re just scared to death. And he greatly comforted Glenna and me. He stayed the whole morning she was in surgery.”

Andy and Frank later worked together on building Saint Anne’s Terrace, a 100-unit residence for the elderly which took seven years to turn into a reality — from 1980 to 1987, when the facility finally opened, after multiple proposals and town hall meetings and architectural plans and interactions with HUD and financial backers and zoning issues.

The process could often get depressing, Smith said, but Frank maintained that all the effort would be worth it. Andy said, “He always had this notion that things are going to get brighter. It might seem dark now, but it’s okay. This is the way it happens. I think he figured out a way to make what was seeming like punishment into reinforcement. And he was right — it always worked out.”

Once Frank retired in 2000, he and Elizabeth had the chance to travel more. They bought a Volkswagen Eurovan and drove along the Lewis and Clark Trail, following the path of the Missouri River and making friends along the way. They traced their family roots across Europe.

Their symbiotic partnership had always been founded, Elizabeth said, upon a general understanding that they were on the same page; they were a team: “It was basically ‘say yes as much as you can,’” she said.

In fact, when asked to recall what they argued about, Elizabeth said the biggest squabble in her memory occurred during their honeymoon: “We had this big discussion about praying—either sticking to the prayers from the prayer book or just having a little spontaneous prayer — and I was for spontaneous prayer.” She stops and laughs. “Kind of boring, isn’t it?”

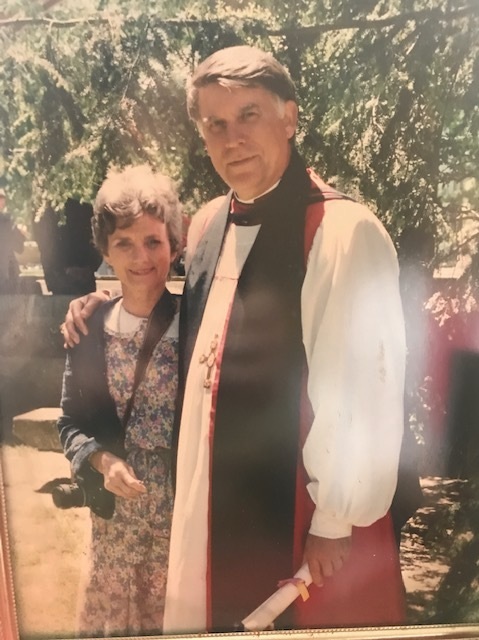

Elizabeth and Frank Allan, courtesy of Elizabeth Allan.

Wooden bowl & fruit, made by Frank Allan.