Reflections on Faith & Reconciliation Across Troubled Waters

By Alexis Hauk

EMBARKING

Ever since she was 12 years old, growing up in Guyana, St. Simon’s parishioner Claudette Seales, now 70, dreamed about visiting Ghana – in part because of the murmurings among family members that this is where her ancestors had originated, before they were forcibly brought to South America as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

Over the decades of her life, Seales moved to the U.S., started a family with her husband, and worked her way through college and a career. For a long time, that impetus to visit Africa lay dormant — until recently, when she came across a blurb about the Ghana Pilgrimage on the Diocese of Atlanta website and decided to apply.

“It wasn’t something that my church sponsored or talked about or told me about. It was just destiny,” she said. The dream had been reignited.

Seales was one of 15 faithful travelers from different backgrounds and experiences across the Diocese who embarked on this year’s pilgrimage to Cape Coast, Ghana, a former hub of the transatlantic slave trade at the end of April – fittingly, a week after Easter Sunday, with its themes of deep despair transforming into hope and absolution. The trip also happened to take place during the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first ship of enslaved Africans in Jamestown, Virginia.

An annual tradition in the Diocese, the Ghana Pilgrimage offers participants the opportunity to confront one of the ugliest facets of history: slavery, and the devastating repercussions of institutionalized racism for subsequent generations in both Western Africa and the Americas.

For centuries, tens of thousands of human beings were ripped from their families, homes and livelihoods and forced into brutal living conditions to build up the wealth of their captors. The city of Cape Coast, Ghana, was occupied at various points by colonizing forces from Great Britain, Portugal, Sweden, Denmark and Holland.

THE DUNGEON

One of the stops on the pilgrimage was Cape Coast Castle, where West African people were held in dungeons before being sold and forced onto ships bound for the Americas.

“Those dungeons or detentions are still standing there like ghosts, as if they want to tell the story of their own brutalities that men and women suffered,” Seales said.

By all accounts, seeing the castle is a core-rattling experience. During a trip to Ghana in 2009, President Barack Obama described his visit to the castle this way: “I’m reminded of the same feeling I got when I went to Buchenwald with Elie Wiesel. You almost feel as if the walls could speak.”

Smithsonian Magazine included this horrifying note about the site: “Guides tell visitors that the walls bear the remnants of the fingernails, skin and blood of those who tried to claw their way out.”

Pilgrimage participant Peggy Courtright, a board member of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing since its inception in 2017, said she had visited several memorial sites in the U.S. which honor the victims of slavery and lynching. But seeing the legacy of racism and its heinous machinery far across the ocean inspired a different level of understanding.

“Confronting the capacity of human beings to not only be stunningly cruel but to systematize it, creating a system that will continue the cruelty, abuse and murder – we’ve seen it happen over and over again in history,” she said, adding that she was surprised by “how much healing happened in all of us. In ways that I wouldn’t have imagined, in ways that made me sob.”

HEAVEN AND HELL

The Rev. Jeff Jackson, rector at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church in Carrollton, said that in contrast to other pilgrimages he’s joined, which involved “basking in the spiritual residue of the goodness of the church” — visiting the home of a holy person, for instance, or a place where miracles were said to have taken place — this trip offered the invitation to delve into something much more challenging: “The chance to stand in the footsteps of my spiritual ancestors who committed atrocities, who committed grave sin.” The church very much participated in, and profited from, the slave trade.

Rev. Jackson said the image that stuck with him most viscerally was the paradox between the dungeon at Cape Coast Castle – “the mouth of hell,” as he saw it – and the haughty regality of the Anglican chapel looming above it. His first thought was that this was a darkly ironic panorama of heaven and hell.

“But then I thought, no: the people who were up there in the Anglican church praising God and taking communion together, all while human lives were being systematically dismantled and dehumanized and brutally tortured — those people up there were not in heaven. That’s a different level of hell. When you are completely aware of the atrocities of humanity and yet you do nothing about them, and in fact you revel in them, that is a totally different separation from God. It made me ponder, what are the ways that we are knowingly or unknowingly perpetuating other atrocities?”

As a white man raised in the south, Rev. Jackson said his fervent interest in, and commitment to, racial reconciliation and community-building has grown out of a willingness to enter into uncomfortable conversations and confront insidious biases and fears planted during childhood.

He remembers growing up in rural Alabama and being exposed to racist beliefs that he later learned to question: “Once you start tapping at that root, you realize how deep the root goes,” he said. This process of wrestling with the sins of the past has informed his understanding of faith.

“We are complex people. We are not just all good. Spirituality isn’t about the warm and fuzzies; it’s confronting the sin that we hold and the sins of those who have gone before us,” he said. “And not denying the truth but entering into it. That’s a core tenet of our faith – repentance. . . Through repentance, we’re healed, if we’re honest.”

HAUNTED AND HALLOWED

The haunted places in Ghana today have become a kind of hallowed ground, as people lay memorial wreaths and pay tribute to the lives destroyed through the devaluation of humanity. As a group, Seales said, “We thanked God for the strength that he gave us as a group to pray, to share our hugs and share our pain, the tears. I think that’s how we got through it. Our group really connected. There was an understanding, every step of the way, that it was not easy.”

Courtright said that when she returned home, someone asked her if the trip was “fun.”

“I said I don’t know how to answer that. Fun wasn’t really the purpose of the trip,” she said. “I expected a lot of pain and anger. But I did not expect that degree of healing, too. We witnessed a lot, and now it’s our job to come back and witness to others.”

These shattering moments of confronting the past and its echoes in the present were intermingled with bittersweet moments of beauty and tenderness – like venturing down the canopy walk through Kakum National park – as well as the warm, welcoming services the pilgrims attended in local parishes, and the reverberations of jubilant music through the sounds of piano, trumpet, drums and voices joined in song.

An equally important facet of the annual pilgrimage is planting the seeds of new relationships. The pilgrims visited six parishes of the Cape Coast Diocese, worshiped with seminarians at St. Nicholas Seminary, and learned from the women’s diocesan ministries. The kindness, generosity and hospitality of those they met, even amid astounding levels of poverty, stood out to the Rev. Dr. Angela Shepherd, rector at St. Bartholomew’s in Atlanta.

Like Claudette Seales, Rev. Shepherd had also dreamed about traveling to Ghana – seeking to shadow her ancestors’ path “and bridge the gap in history.” The trip was especially poignant because she was able to share the experience with her adult daughter, who joined the Diocese cohort.

HONORING ANCESTORS

The most moving part of the trip for many was the visit to the Last Bath or River of Remembrance in Assin Manso, where those who had been kidnapped were taken before being sold.

Seales said that she was able to honor her ancestors by leaving a note on the memorial wall at the Last Bath, after which she received her African name, Akua. “When we returned and met at the Bishop’s Chapel, he welcomed me as Akua. How can I ever forget that?’”

Rev. Shepherd brought a portrait of her great-great grandmother, Daphene Scales, who was born in 1836 and endured enslavement. In the picture, Daphene clearly bears the deep physical and mental scars of enslavement. “Her eyes look so sad,” Shepherd said. “I placed the photo against the wall in each place where the women were held in Cape Coast Castle and observed a moment of silence.”

At the Last Bath, Rev. Shepherd stood alongside three other women who had also descended from enslaved people, including her daughter. She unfolded the photo of Daphene and placed it in the river.

“It swirled a bit before being taken under and carried away,” she said. “Part of my mission was to bring her home, and I imagined her eyes smiling and rejoicing then.”

The tears, and the opportunity to honor these relatives, were a profound catharsis for Rev. Shepherd. “I experienced a powerful sense of God’s presence. It was a spiritual moment of reconciliation with history and healing: one that rivals none other in my life.”

The palpable sense of survival, and of the enduring human spirit, followed Rev. Shepherd home. As she put it, “I am a descendant of those who survived the walk to the Last Bath, the transatlantic journey, and chattel slavery. I am because they were. Perseverance was born.”

The steeple on Christ Church Cathedral, Anglican Diocese of Cape Coast taken from the auction room in Cape Coast Castle where slaves were sold.

Walking sacred ground: The path to Assin Manso, to the river where captives were bathed before being sold.

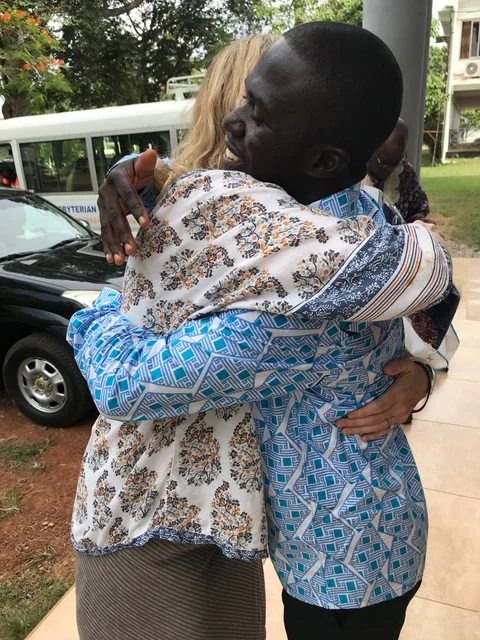

The Rev. Father Theo Odametey and the Rev. Canon

Dr. Sharon Hiers greet one another.

All photos courtesy of the Rev. Canon Dr. Sharon Hiers.